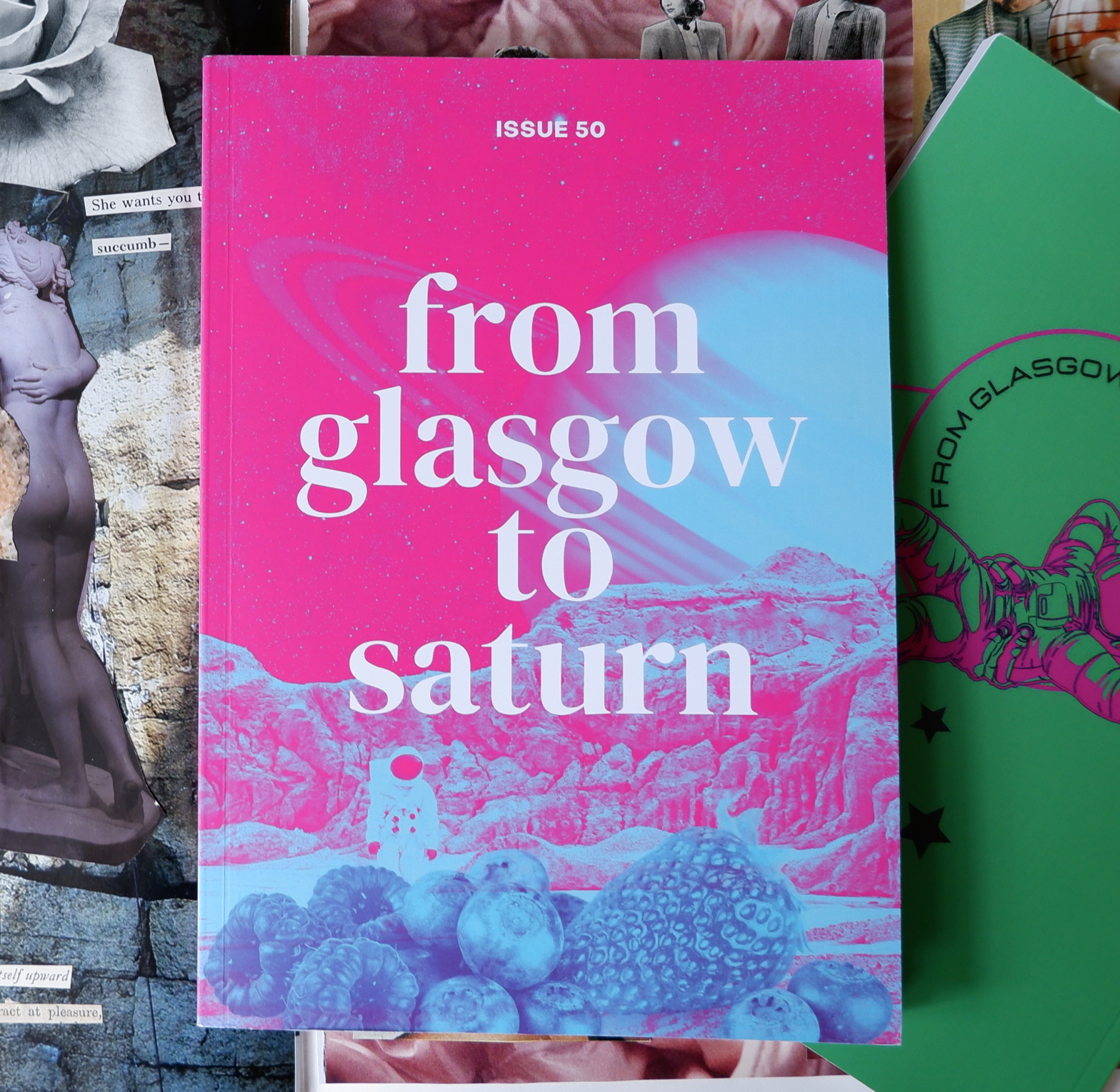

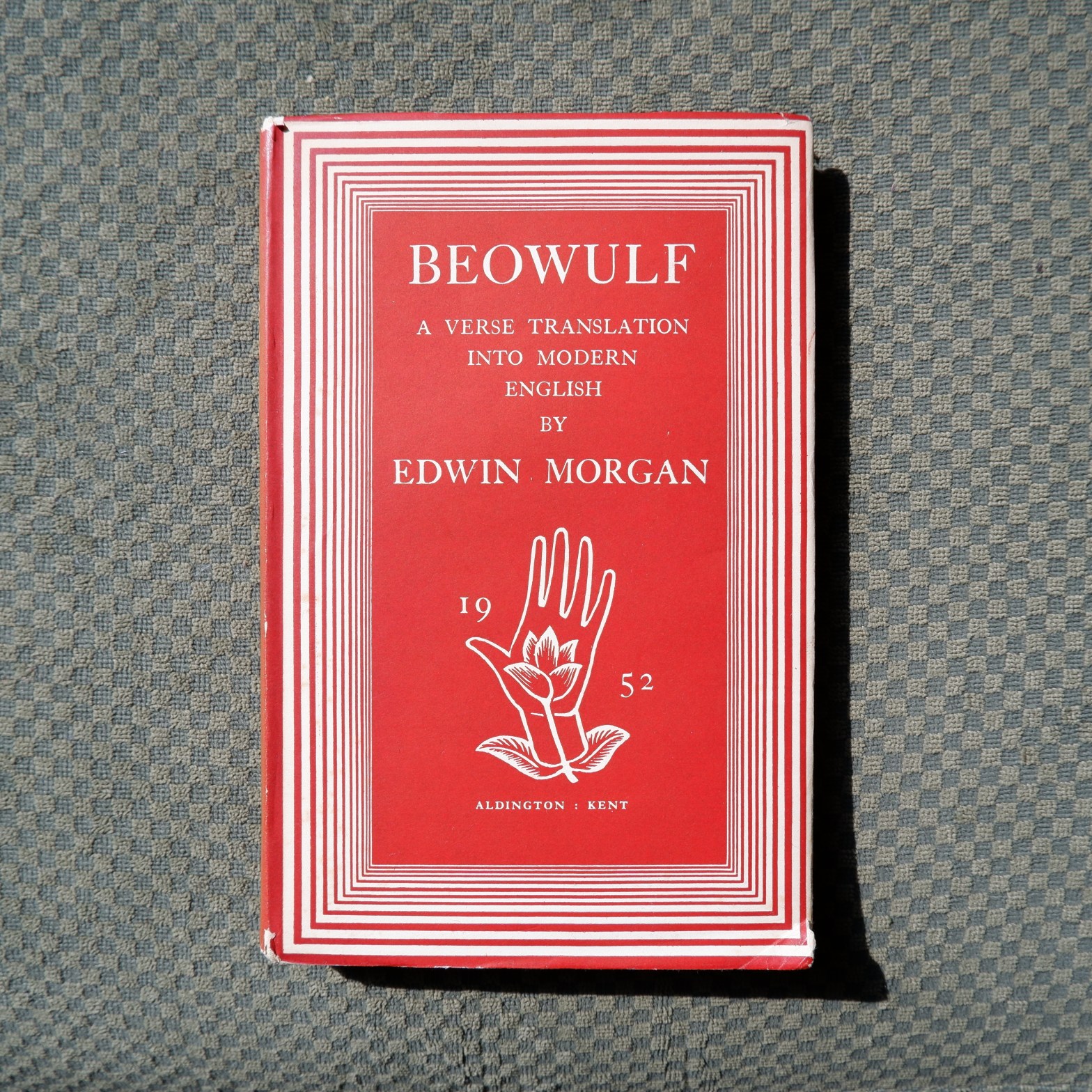

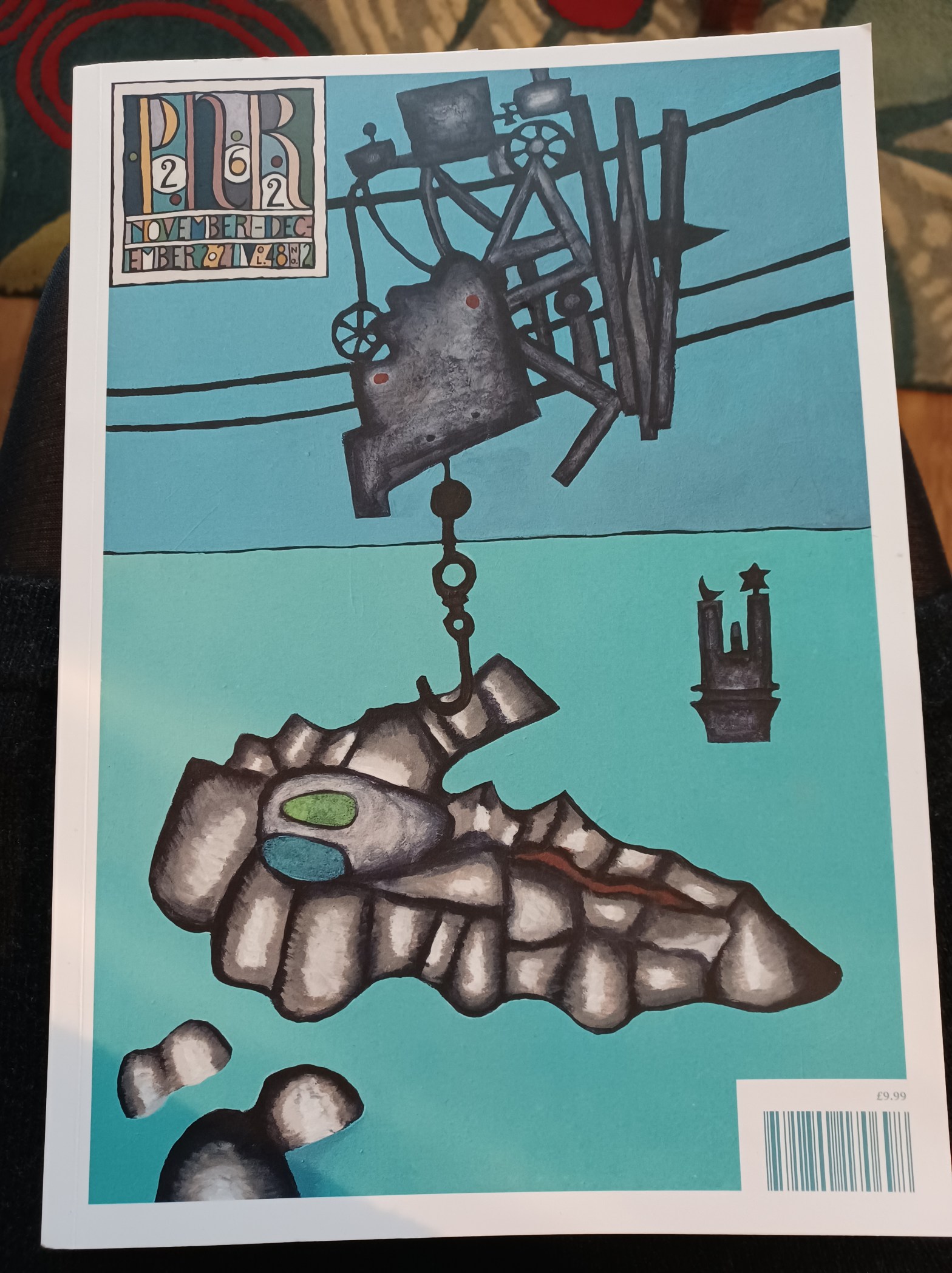

The 50th Anniversary issue of the Glasgow Journal From Glasgow to Saturn has a selection of collage poems by me in it. The journal takes its name from a 1976 poetry collection by Scottish Makar, poet and lecturer at the University of Glasgow, Edwin Morgan, and this edition is something of a tribute, or a response to him.

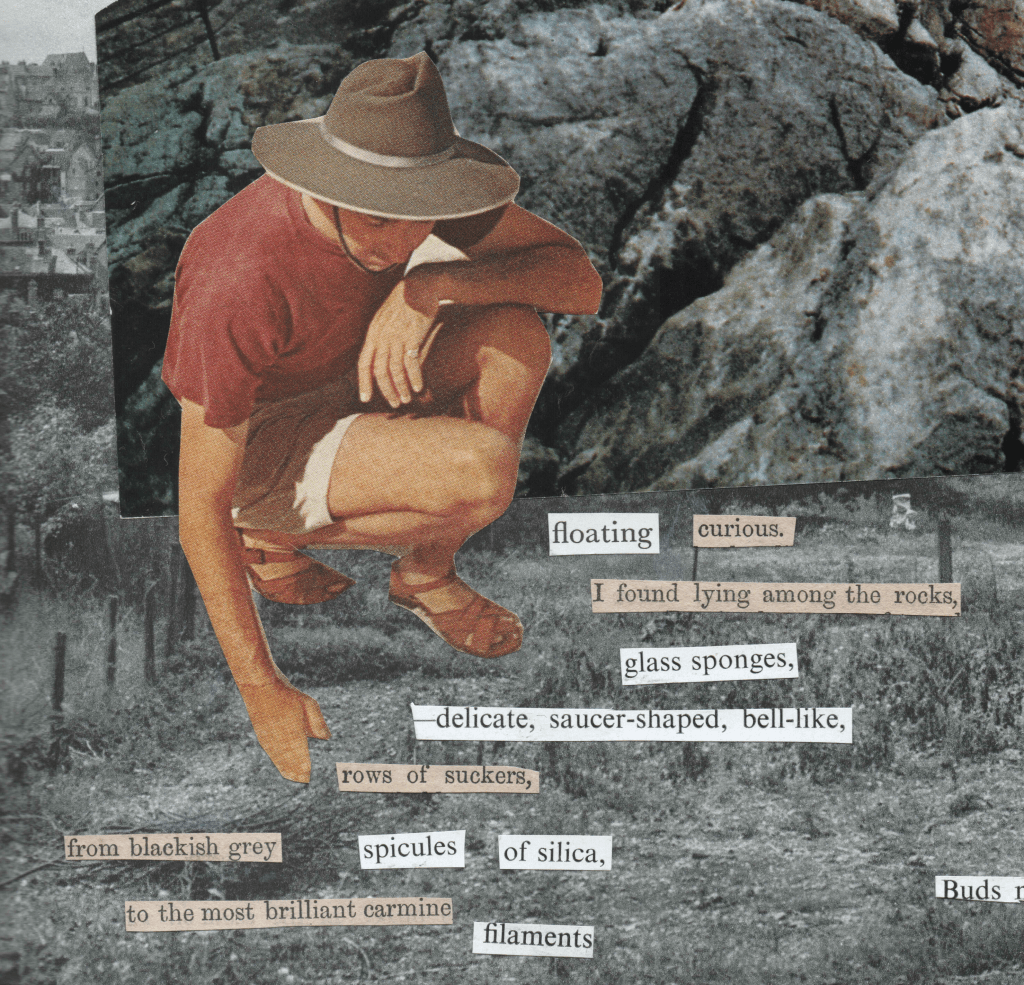

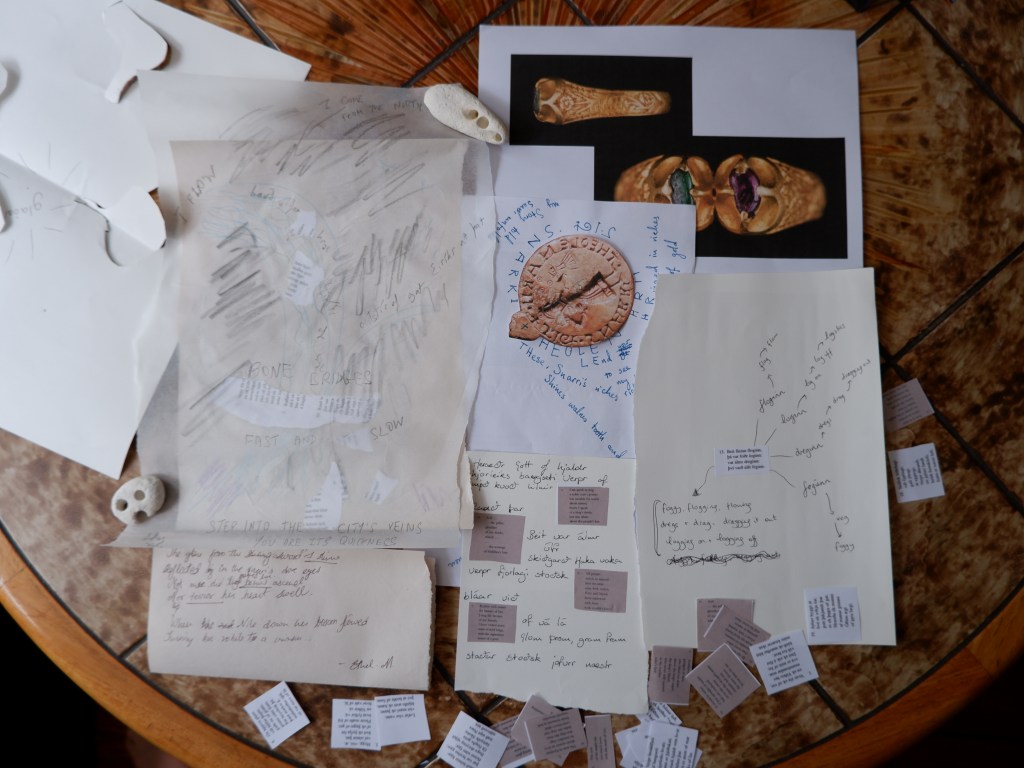

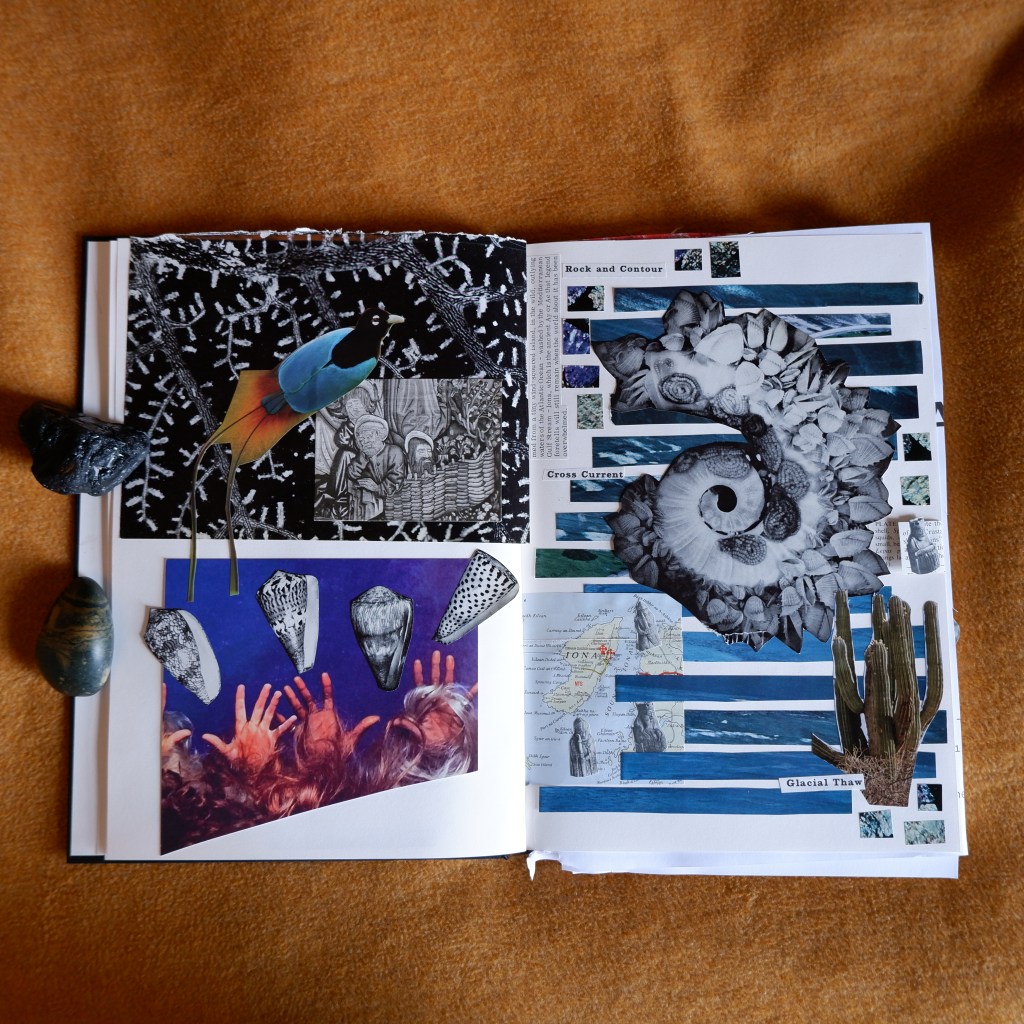

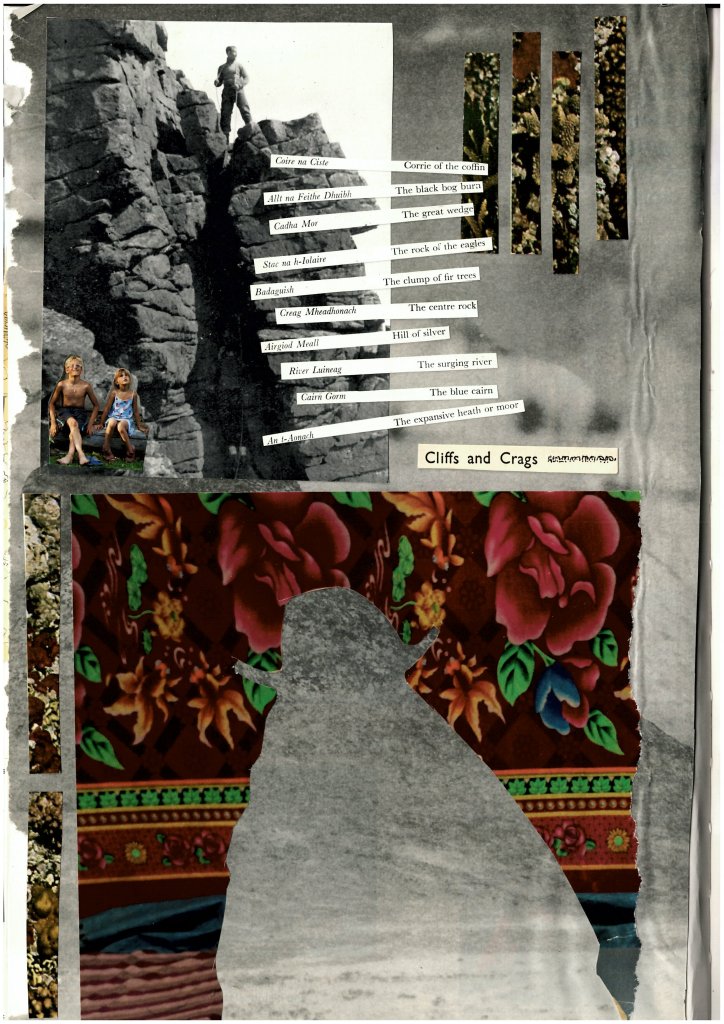

My poems for the journal – ‘Floating Curious’, ‘She wants you to glide’, and ‘Cliffs and Crags’ – are all ‘collage poems’, works of visual poetry that combine found text and imagery to create something new and surreal. I started creating collage poems during the pandemic, but it was really a research fellowship working with the scrapbooks of Edwin Morgan at the University of Glasgow Archives and Special Collections, that saw this method of poetic making flourish and develop.

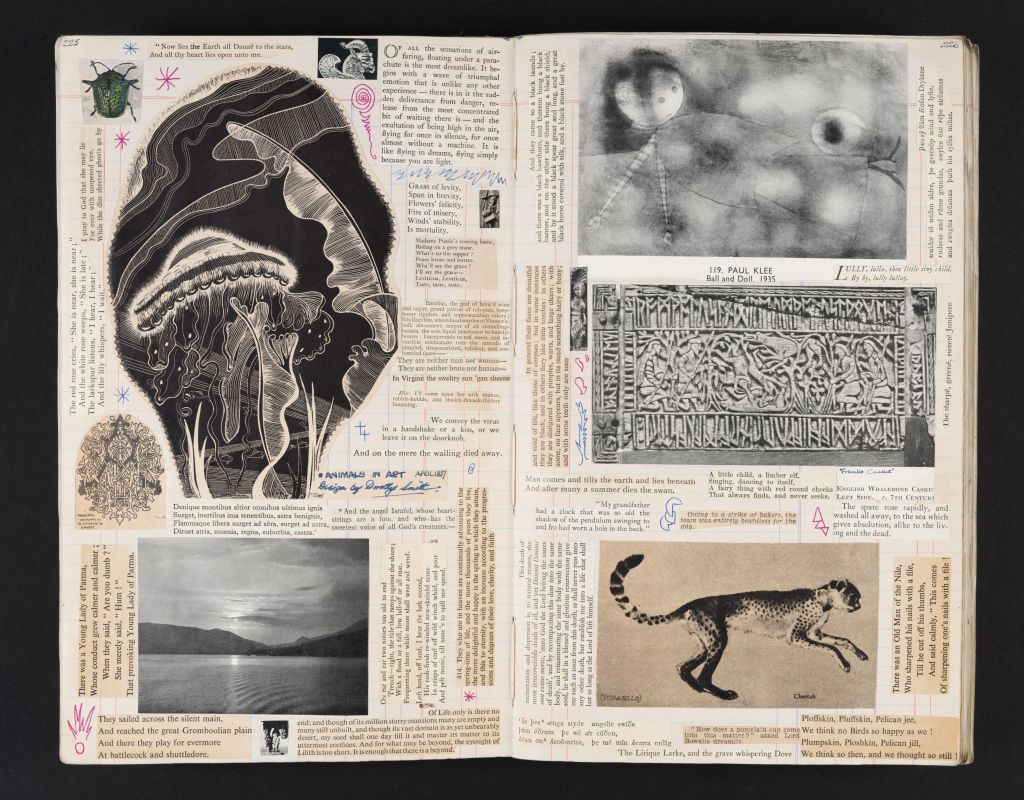

Morgan worked on his scrapbooks between 1931 and 1966. They are huge compendiums of literary quotations, found imagery, newspaper clippings, Morgan’s own drawings and dream journals; vast, tentacular maps of the poet and translator’s creative mind at work. It was a struggle to make sense of them as a researcher, but creatively poring over the pages had me fizzing to try out the process myself. I bought a hardbound sketchbook, a pair of scissors, and a stick of glue from Cass Art in the centre of Glasgow and started gathering printed materials with which I might create my own scrapbooks during the evenings of my fellowship.

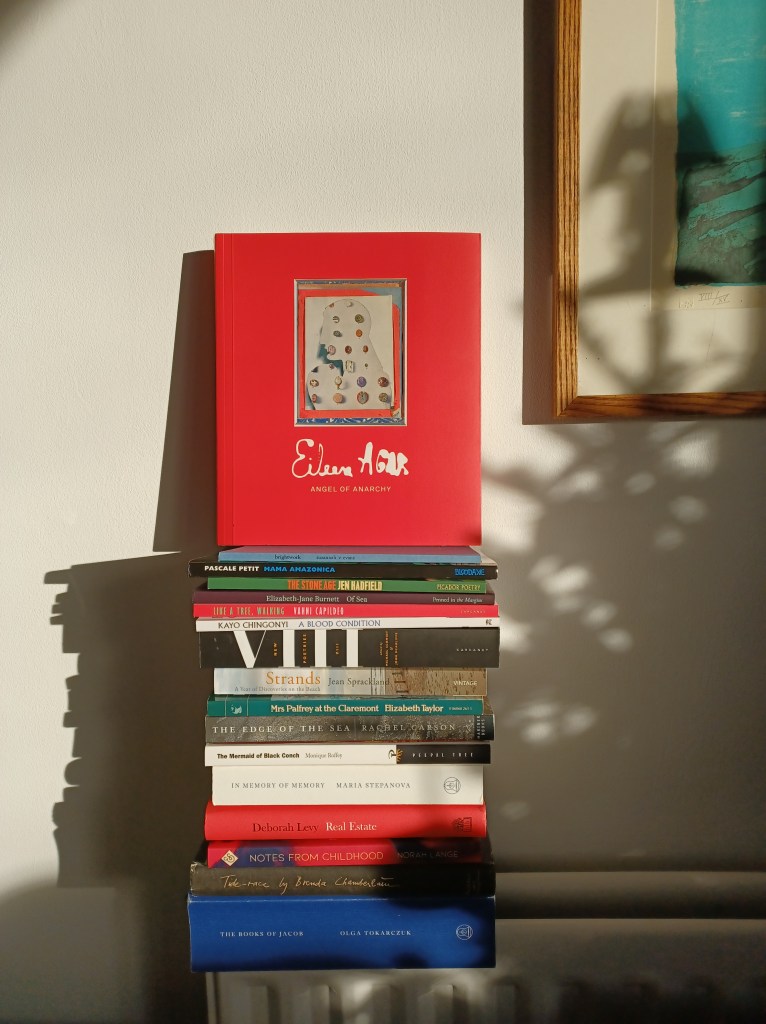

Working with Morgan’s scrapbooks has encouraged an interest in collage and visual poetry more broadly. I have been following 3am Magazine’s Poem Brut series, and really enjoyed reading Emma Filtness’s incredible collection The Venus Atmosphere, published by Steel Incisors (visual poetry press ‘with teeth’). One of my friends is also a wonderful collage artist and constant source of inspiration, Laura Mipsum, and in Manchester I have been to a Collage Club run by Local Hotel Parking, which introduced me to the joys of a good scalpel and cutting mat! I’m also grateful to Johanna Green, who not only welcomed me to Glasgow by introducing me to the delicious Little Italy Pizzeria but also encouraged me to think a bit more about visual poetry.

If there are any visual poets or collage artists you follow, I would love to hear about it in the comments below!