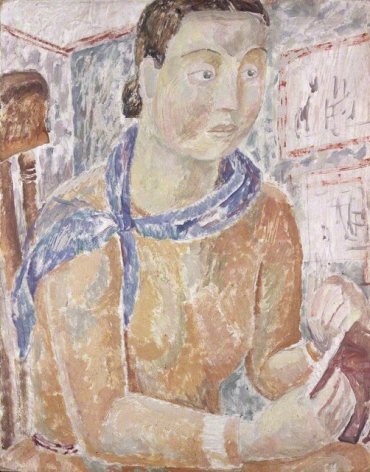

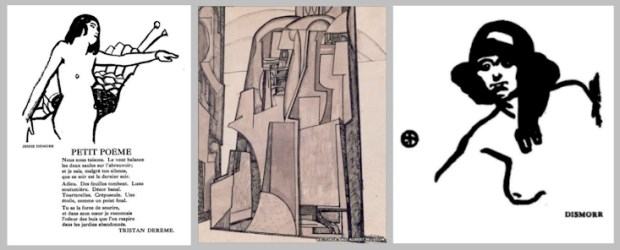

A decade ago now, I had an article based on some very early research published with Flashpoint Magazine. The piece was about the fascinating artist and writer Jessie Dismorr, comparing her experimental pieces for Blast! magazine with some of Virginia Woolf’s writing. I’ve just discovered that the Flashpoint website is now down, and as the piece seems to continue to attract the interest of people working on Dismorr, I decided that I’d post the essay here so that it is accessible somewhere.

Kate Lechmere, a former lover of Wyndham Lewis, famously described Jessie Dismorr and fellow female Vorticist, Helen Saunders, as two ‘little lapdogs who wanted to be [Wyndham] Lewis’s slaves and do everything for him.’[1] In writing this article I want to overwrite this narrative of insignificance and marginalisation with a more powerful and suggestive one: while the unnamed narrator of Jessie Dismorr’s ‘June Night’ (Blast! War Number 1915) begins by waiting compliantly with ‘happiness and amiability tucked up in [her] bosom like two darling lap-dogs’ (in a possible retaliation to Lechmere’s dismissive comments) she soon rebels against her male chaperone, escaping from the ‘unmannerly throbbing vehicle’ of the omnibus to wander in the ‘mews and by-ways’ alone, no longer happy or amiable or a slave. In reading the radical prose vortices which Dismorr contributed to the Blast! War Number for all of their richness I will argue that Dismorr’s position as a Vorticist, a writer and a modernist, deserves greater critical recognition.

Dismorr’s notoriety rests upon her status as an artist working within the modernist movement known as Vorticism: a ‘genuine avant-garde movement having its own identifiable form of geometric abstraction and its own vibrant and aggressive magazine, Blast.’[2] Dismorr was a signatory of the Blast Manifesto in 1914, she contributed a selection of paintings, poems and ‘vortices’ to the 1915 War Number and exhibited with the Vorticists until their final exhibition as Group X in 1920. [3] As a female artist within a movement which Wyndham Lewis later claimed ‘was what I, personally, did, and said, at a certain period,’ it is unsurprising that Dismorr has been marginalised and largely invisible within histories of modernism. [4] While extensive work has been done to provide a study of Dismorr as an artist, this article will explore the particular significance of Dismorr’s prose writings in Blast and their relation to the feminist and metropolitan cultures of her day.[5] Despite the limited body of her writing, with literary contributions to the modernist magazines Blast (1914-1915), The Little Review (1918-1919), The Tyro (1922),and The London Mercury (1935), Dismorr’s continued involvement in radical avant-garde movements is testament to her social and cultural commitment to, and engagement with, her historical moment.

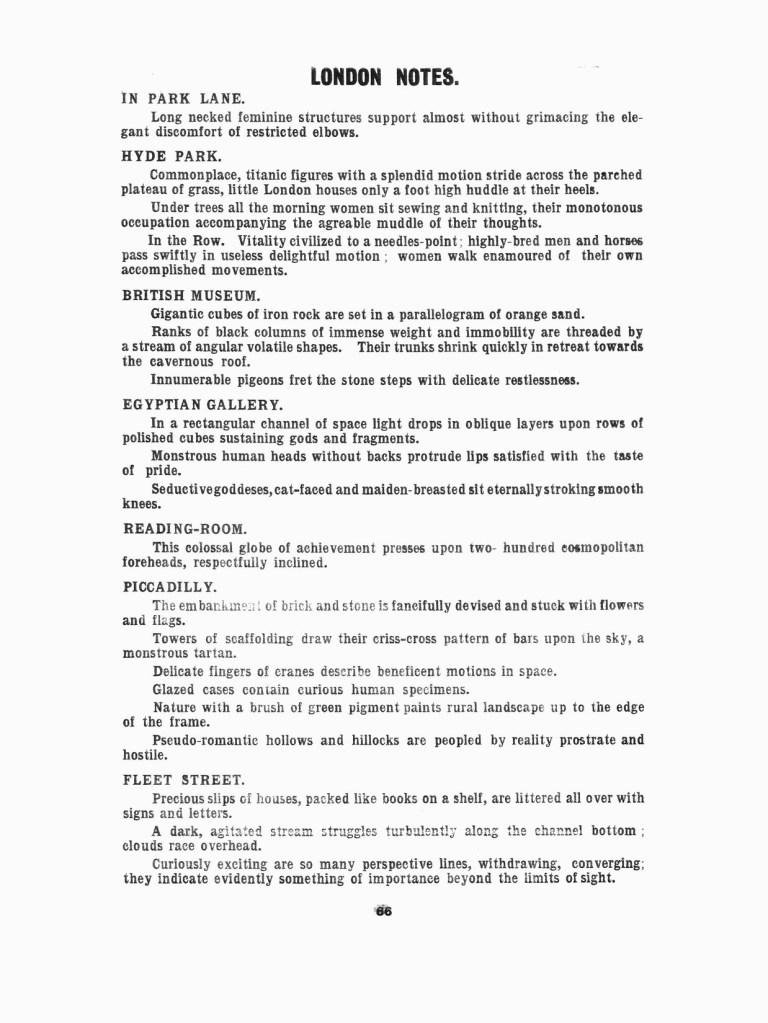

My focus will be on the two prose vortices Dismorr contributed to Blast, ‘London Notes’ (p.66) and ‘June Night’ (pp.67-68), and their relationship to the city of London. ‘London Notes’ presents us with a series of abstractly sketched descriptions of locations in the city, taking us from Park Lane to Fleet Street via the British Museum. The prose vignette, ‘June Night’, begins with the female narrator being picked up by a man named Rodengo: in the company of her ‘chaperone’ she heads out into the city on the No.43 bus, but the narrator soon gets bored of the Romanticism of her companion and escapes from the vehicle, and Rodengo, to wander the unfamiliar streets and neighbourhoods of London alone. Both involve a drift across the city: the one disembodied, the other embodied in a female narrator. In order to present the former as a mapping of a patriarchal city, and the latter as a feminist rewriting of this city through walking, I will make comparisons with the London Virginia Woolf maps in The London Scene (1931-32) and A Room of One’s Own (1928). Although this writing is separated by more than a decade and the First World War, Dismorr (1885-1939) and Woolf (1882-1941) lived in the same metropolitan context and may even have moved within some of the same creative circles. As female artists in London, financed by private incomes, and moving within pre-dominantly male circles, Woolf and Dismorr write from comparable contextual perspectives.

[1] Quentin Stevenson

[2] Paul Edwards, ed., Blast! Vorticism 1914-1919 (Burlington, USA, 2000) p.9

[3] Wyndham Lewis, ed., Blast 2: The War Number (London, 1915) subsequent references will be cited parenthetically in the text.

[4] Edwards, Blast! Vorticism 1914-1919 (2000) p.9

[5] See Catherine Heathcock, ‘Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939): Artist, Writer, Vorticist’ (unpublished thesis, Birmingham University, 1999)

Mapping the Patriarchal City

In Richard Cork’s major summary of Vorticism he described Dismorr’s ‘naivety’, writing that it would be easy to dismiss her work as a ‘second-rate pastiche of other artist’s ideas’.[1] By looking closely at how Woolf chooses to present an overwhelmingly masculine vision of London in order to expose gender prejudices, I will show that Dismorr is acutely aware of the masculine bias of Vorticism: rather than merely imitating, Dismorr appropriates and manipulates Vorticist forms in order to construct her own feminist vision of the city.

In ‘Reconceptualizing Vorticism’ Deborah Cherry and Jane Beckett note that after 1900 there were a number of social inquiries, guidebooks and route maps produced about London (C. Booth 1889-1903, W. Besant 1899, C.F.G Masterman 1903, G.R Sims 1909); evidence of the effect grand town plans, such as George-Eugène Haussmann’s redesigned Paris, had on more localised social interest. Francine Proseintroduces Virginia Woolf’s six essays in The London Scene, originally written for Good Housekeeping (1931-1932), by describing them as ‘a practical Baedeker to the city’.[2] However, they form a guidebook with a very considered purpose and an underlying polemic. Directed at Good Housekeeping’s largely female audience, Woolf reveals a city demarcated by gender and class. Woolf’s essays move through spaces of industry, commerce, religion and politics, to present us with an overwhelming sense of masculine authority and female exclusion. Moving from ‘The Docks of London’ to ‘Abbeys and Cathedrals’, ‘the House of Commons’ and eventually to ‘Great Men’s Houses,’ Woolf’s essay titles and subjects demonstrate that the city is overwhelmingly the province of men. It is men who are commemorated by the Church, our political system and as literary heroes, and it is men who are represented in the vast powers of industry and the commerce of the ‘Oxford Street Tide’. There is a complete absence of women of power in the city; the traditions of privileged patriarchy are perpetuated in the city’s public and private spaces.

Similarly, in ‘London Notes’, Dismorr produces a chorographical map of the city which becomes her own guidebook and social critique of London. Each section is headed, like a map, by a familiar location but the prosaic fragment which underlies it goes beyond superficial details and begins to expose the power structures and biases which are at work in the brickwork and monumentality of the city. Dismorr’s surreal and abstract fragments in ‘London Notes’ also map-out male control of public city spaces, her prosaic headings mirroring many of Woolf’s essay titles: as Dismorr moves from one of the most expensive addresses in London, ‘PARK LANE’, to the haven of scholarship and academia that is ‘THE BRITISH MUSEUM’ and finally finishes with addresses of commerce and industry, ‘PICCADILLY CIRCUS’ and ‘FLEET STREET’, we can read a comparable vision of patriarchal exclusivity in Woolf and Dismorr’s writings.

The monuments which Woolf focuses upon in The London Scene are also literary and show her trying to find reflections of her own identity in civic spaces. In Westminster Abbey we move from the tombs of Gladstone and Disraeli, to Chaucer, Spencer and Dryden: ‘Here are the dead poets, still musing, still pondering, still questioning the meaning of existence.’[3] A personal city is also being mapped in ‘London Notes’ and the narrative of ‘June Night’. Dismorr’s ‘Notes’ are interested in the city as a creative space endowed with a literary history comparably weighted towards men. ‘PARK LANE’ is a street celebrated by Victorian male novelists such as Thackeray and Trollope.[4] The legacy of ‘FLEET STREET’ as a space of publishing houses is echoed in Dismorr’s description of ‘Precious slips of houses, packed like books on a shelf’ which ‘are littered all over with signs and letters’. The street itself has become a text, one which literary canons suggest is written by men. Dismorr’s ‘Notes’ are also gesturing towards her claims to literary heritage as a woman; her writing registers a consciousness of the encroachment she is making upon a male economy.

The most significant location which Dismorr explores is that of the ‘BRITISH MUSEUM’. In A Room of One’s Own Woolf visits the Reading Room of the British Museum in order to research the history of women’s literature, but finds a history written exclusively by men.[5] The Reading Room, as a metaphor for the Academy, is a space dominated by men in its textual content and in its body of visitors: ‘there one stood under the vast dome, as if one were a thought in the huge bald forehead which is so splendidly encircled by a band of famous names.’[6] The huge bald forehead personifies the Reading Room as an old, authoritarian male and suggests its out-dated prejudices. Woolf becomes a ‘single but harassed thought’ as she reads, disillusioned with her sense of increasing exclusion and alienation.[7] Woolf’s summation of her experience in the Reading Room is that it is ‘distressing’, ‘bewildering’ and ‘humiliating’; a hostile environment for a woman and writer.[8]

Woolf’s feminist use of the anecdote of the Reading Room to expose female exclusion from intellectual spheres draws out the hostility in Dismorr’s own penetration into this space. ‘THE BRITISH MUSEUM’ is the only interior space Dismorr explores in ‘London Notes.’ Dismorr’s progressive movement through the public space of the ‘EGYPTIAN GALLERY’ to the more private and privileged space of the ‘READING ROOM’, reflects the greater intellectual access opening up to women. Heathcock’s research highlights that it was not easy for women to gain access to the Reading Room and an application process was necessary. Dismorr applied to the British Museum Library at the age of 21, which was the minimum age of application, and she made her first visit on the 13th March 1906 and renewed her six monthly ticket frequently up to 1925.[9] The ‘Notes’ reflect Dismorr’s personal development as an artist and her own negotiation of access to these exclusive and predominantly male spaces. Like Woolf, Dismorr comments on the ‘foreheads’ of intellectualism: ‘The colossal globe of achievement presses upon two-hundred cosmopolitan foreheads, respectfully inclined.’ There is an intimidating grandeur in this interior space which is typically the domain of the male academic. The ‘achievement’ which ‘presses’ upon Dismorr becomes an oppressive male force, reminding her of her transgression into what has previously been deemed an exclusively male space. Dismorr’s inclusion of this landmark is an assertion of the access she has gained as an academic and an artist. However the Reading Room is still only a research space. Women have a new access to the city and its creative places but Dismorr must move from the disembodied observation of this to the personal narratorial voice of ‘June Night’ to actively use the freedom she has forged for herself.

[1] Richard Cork, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age ,Volume 1: Origins and Development and Volume 2: Synthesis and Decline (London, 1976) p.415

[2] Woolf, The London Scene: Six Essays on London Life (New York: Ecco, 2006 (1932)) p.x

[3] Woolf, The London Scene (2006) p.45

[4] Christopher Hibbert and Ben Weinreb, ed., The London Encyclopaedia (London: Book Club Associates, 1985 (1983)) p.583

[5] Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (2004) p.31

[6] Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (2004) p.30

[7] Ibid, p.34

[8] Ibid, p.35

[9] Heathcock (1999), p.105

Male Monumentality

The London Woolf writes is marked by masculine symbols of power which reinforce male demarcations of space. In A Room of One’s Own Woolf walks her thoughts about women writers through the city and this walking and thinking is punctuated by male monuments, the city is dedicated to, and dominated by, this male assertion of power. A reflection upon the ‘imperial glory’ of the Admiralty Arch leads Woolf to look more critically at what these monuments represent: ‘the lack of civilization, I thought, looking at the statue of the Duke of Cambridge […] with a fixity that they have scarcely ever received before.’[1] Woolf’s ‘fixity’ upon this statue is particularly significant as it rewrites the male gaze of Peter Walsh in her fictional Mrs Dalloway:

Striding, staring, he glared at the statue of the Duke of Cambridge. […] Still the future of civilisation lies, he thought, in the hands of young men like that; of young men such as he was, thirty years ago.[2]

While Peter reads civilisation into this statue, Woolf perceives the lack of it. As Peter moves on, his walk and his thoughts are punctuated by other statues, Nelson, Gordon, Havelock; this monumental city is adapted to his thinking and reveals everywhere reflections of himself and his ideals. In fixing her attention upon these male monuments Woolf exposes a London which is adapted to the vision of men and suggests that perception and the gaze are gendered, giving her the power to present alternative readings of the city.

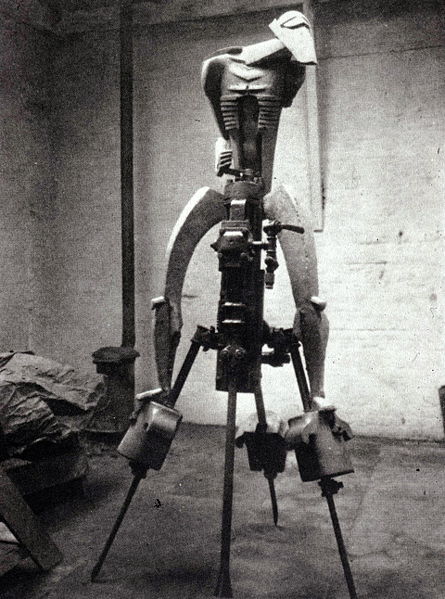

In Rock Drill (1913) and Venus (c.1914-1915) the Vorticist, Jacob Epstein, presents us with his antithetical vision of modern man – part human, part inimitable machine, and the archetypal woman – slumped and hunched in a passive pose. In ‘Monologue’ (p.65), a poem which precedes ‘London Notes ’in the Blast War Number, Dismorr plays with these visions of the masculine and the feminine Vorticist. The female body in ‘Monologue’ is subjected to the ‘new machinery’ of Rock Drill: the poem’s subject becomes automated, mechanic, with ‘arrogant spiked tresses’ and ‘chains of muscles’, yet she also struggles with the corporeal apathy of Venus as she lies a ‘slack bag of skin’; the two corporeal identities (slack skin and chain muscle) are seemingly at impossible odds with each other. ‘Monologue’ is evidence of Dismorr’s negotiation of the gender archetypes implicit in Vorticism’s aesthetics and her struggle with their aggressively binary nature. In ‘London Notes’ Dismorr’s vision of the monumental city also addresses this binarism to expose a London adapted to masculine aesthetics and ideals.

In the ‘Notes’ Dismorr plunders the possibilities offered by the lines and forms of Vorticism to present the streets, buildings and monuments of London as abstract line drawings. In fragments and shards organised by location, the prose is arranged in collections of lines which are as volatile and aggressive as a Vorticist painting; she creates a highly stylised and radical prose which reflects the aesthetics of her movement. The ‘Notes’ seek out the angular, abstract lines of Vorticism in the built environment: the classical exterior of the British Museum becomes, ‘Ranks of black columns of immense weight and immobility […] threaded by a stream of angular volatile shapes.’ The clipped sentences and the forms sketched out, fit with the Vorticist aesthetic and yet the feminine entity which shares this space registers an uneasiness. The ‘Notes’ begin in ‘PARK LANE’ where, ‘Long necked feminine structures support almost without grimacing the elegant discomfort of restricted elbows’. The uneasiness here is evident in the anthropomorphic corporeality of these monuments which is at odds with the regular, machinated, and inanimate lines of Vorticism. This isn’t merely assimilation and imitation: the ‘feminine structures’ become a reading of the ‘restricted’ woman within the city and her refusal, or her inability, to adapt her body to the new aesthetic. The juxtaposition of the feminine and the Vorticist is a means for Dismorr to make visible the masculine biases inherent in the movement.

In ‘HYDE PARK,’ ‘Commonplace, titanic figures with a splendid motion stride across the parched plateau of grass,’ and ‘highly-bred men and horses pass swiftly in useless delightful motion’ in poses of confidence and statuesque assurance, while the women simply ‘sit sewing and knitting, their monotonous occupation accompanying the agreeable muddle of their thoughts.’ The feminine continually fails to fit into abstract patterns of lines and shapes; it stands out for its difference in this monumental vision of the city. Described in mundane or non-abstract terms Dismorr also ironically points to the way in which women are marginalised or trivialised in society. Despite the overall Vorticist aesthetic in ‘London Notes’ the troublesome feminine entity suggests that Dismorr is simultaneously calling this aesthetic into question and fighting to give her own feminist reading of the city visibility beyond those ‘perspective lines, withdrawing, converging’ and beyond ‘the limits of sight.’

[1] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (London: Penguin Books, 2004 (1928)) p.45

[2] Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, ed., Stella McNichol (London: Penguin Classics, 2000 (1925)) p.55

Un-mapping: The Dèrive

Criticism on women writers walking the streets of the modernist city continually focuses upon the Parisian flâneur and Walter Benjamin’s theorising of the city as a model. In their studies of women writing about walking in the early half of the twentieth century, Janet Wolff, Rachel Bowlby, and Elizabeth Wilson use this context to establish a genre of feminist literature.[1] However it continually leads them to the conclusion that the female ‘flâneuse’ is ‘rendered impossible by the sexual divisions of the nineteenth century’.[2] If this criticism is a walk, as Bowlby suggests, then it moves in a circle. The literature of these women is made ‘invisible’ by its inclusion within a gender-exclusive discourse. For Dismorr, the walk is more than just ‘flânerie’ and the detached observation of society from the streets: through diversions into unplanned routes the walk has the power to affect a re-mapping of gendered city-space, diverging from masculine routes to claim new female spaces.

Writing for the Situationist International, Guy Debord explained the theory of the ‘dérive’ (1956) as a ‘mode of experimental behaviour’:

In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there,[3]

As Debord explains, the dérive makes ‘progress’ possible by ‘breaking through fields where chance holds sway, by creating new conditions more favorable to our purposes.’[4] The dérive recognises that cities are ‘rich centers of possibilities and meanings’ with data that can be read and repurposed; by enacting a kind of Vorticist dérive, Dismorr is able to repurpose the data of the modernist city for her female narrator, offering her a liberating ‘interlude of high love making.’[5] The walk is a means of enacting emancipatory, as well as physical, progress through city spaces. Although at the beginning of ‘June Night’ the narrator is only able to watch the city passively in the company of her chaperone through the windows of the bus – her ‘desires loiter about the silent spaces’ from a distance – in the second half of the narrative her desires physically inhabit and engage with the city space as Dismorr’s narrator breaks from the planned route to make her own dérive.

The narrator’s journey in ‘June Night’ is initiated by the mediation of man and machine. Rodengo is the chaperone who frees the narrator from her ‘little dark villa’ which has become claustrophobic. While she waits for him, ‘with happiness and amiability tucked up in my bosom like two darling lap-dogs,’ she is a subservient woman waiting to be a ‘lap-dog’ to a man. But the narrator’s eventual rejection of this man and the assertion of her independence becomes a powerful act of rebellion. The narrator explains with irony and a new rhetorical power: ‘Rodengo, you have a magnificent tenor voice, but you bore me. Your crime is that I can no longer distinguish you from the rest of the world.’ This rebellion is only made possible through the dérive and its un-mapping of the male city.

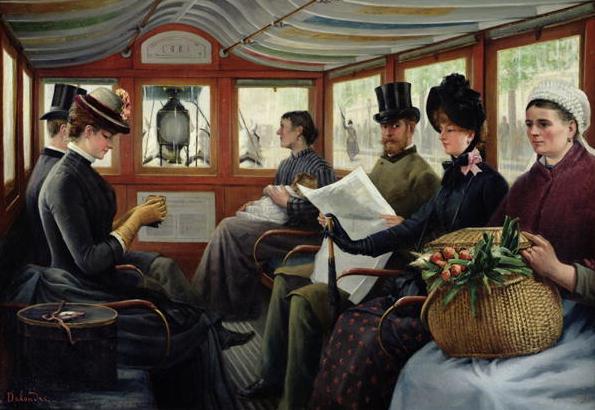

Rodengo and the narrator begin by getting on the omnibus, a symbol of modernity and social mobility:

No 43 bus; its advertisements all lit from within, floats towards us like a luminous balloon. We cling to it and climb to the top. Towards the red glare of the illuminated city we race through interminable suburbs.

From ‘suburb’ to ‘city,’ Dismorr’s narrator gains greater visibility and is taken from the female domestic space of her home towards the male-dominated mercantile centre. Heathcock notes the significance of the seat at the top of bus, ‘which still carried connotations from the late nineteenth century and was viewed as characteristic of an “advanced” woman’.[6] Dismorr’s narrator climbs to the top where she can view the city and be visible within it. The bus which ‘floats towards us like a luminous balloon’ is representative of the rise of the woman, whose ascent is facilitated by this symbol of modernity. The movement to this prime position is not easy; Dismorr’s narrator must ‘cling to’ the bus, and the vehicle is volatile, like the social and public position of women.

However Dismorr’s narrator soon comes to reject the bus too, dismissing it as an ‘unmannerly throbbing vehicle.’ While the bus offers women movement through city spaces it is still a mediator between body and street. The narrator becomes increasingly frustrated with her position of obscurity within the crowds and the bus’ control over her trajectory:

Now we stop every moment, the little red staircase is besieged. The bus is really too top-heavy. It must look like a great nodding bouquet, made up of absurd flowers and moths and birds with sharp beaks. I want to escape; but Rodengo is lazy and will not stop warbling his infuriating lovesongs. Ribbons of silver fire start into the air, and twist themselves into enormous bows with fringes of tiny dropping stars. Everybody stands up and screams. These people are curious, but not very interesting; they lack reticence.

The gorgeousness of the language here, of metaphor and simile, registers the narrator’s growing frustration with the hyperbole and sensory overload the bus. Everything here seems synthetic, surreal and overly decadent, the narrator admits that the experience makes her ‘too emotional:’ it is ‘cool normality and classicalism’ which tempt her, and ‘spacious streets of pale houses.’ When the narrator escapes from the bus she finally becomes an active protagonist in the city-spaces she longed to inhabit from the bus windows. Indulging in her civic desires and defiantly making herself visible within these spaces she is now ‘half-sordid, half-fantastic;’ aware of the implications of her transgression but also empowered by it.

Dismorr’s narrator’s dérive is an act of protest against the restrictions on women in public spaces, it concludes with the narrator’s assertion that she now makes her own way through the city:

Rodengo, you have long disappeared: but I think of your charm without regret. I have lost my taste for your period. The homeward-going busses are now thronged. Should I see you, I shall acknowledge you with affection. But I am not returning that way.

She rejects the route proscribed for her by her former guide and no longer feels the need to be led by a chaperone. However when the ‘refuge’ Dismorr’s narrator finds in ‘mews and by-ways’ transforms her, an ambivalence is evident: ‘Creeping through them I become temporarily disgraced, an outcast, a shadow that clings to walls.’ Dismorr’s character moves cautiously as though she is aware of the danger which underlies her journey. The ‘shadow which clings to walls’ recalls the prostitutes or ‘passantes’ of flânerie and the Surrealist narrative of pursuit. [7] In the street she is in danger of being captured by the male gaze. As a ‘stray’ and an ‘outcast’, the walk registers a brave transgression: whilst offering freedom, it also destabilises the comfortable position the narrator occupied as a woman of class. As Dismorr asserts: ‘At least here I breathe my own breath;’ the freedom negotiated for women is not absolute but it does offer a progressive movement forward. Dismorr’s narrator can only be ‘temporarily’ disgraced; eventually she ‘must’ go ‘back to the life of the thoroughfares to which’ she belongs. While the journey made her an ‘outcast’ her return is to a definite sense of ‘belonging:’ ‘I must get back to the thoroughfares to which I belong’ she tells us. For all the rebellion of her dérive ultimately this freedom is only, as Dismorr describes it, ‘an interlude of high love making’: a momentary fantasy.

While the emancipation the dérive of ‘June Night’ offers women may be momentary rather than absolute, by changing her narrator’s course and allowing her to wander into unplanned diversions and empty streets, Dismorr is able to re-write the patriarchal city she mapped out in ‘London Notes’. If ‘London Notes’ presented us with a patriarchal map of the city mediated by the aesthetics of Vorticism, then ‘June Night’ navigates an alternative map of competing aesthetics and artistic movements, to show the writer’s personal progression through the city’s rich cultural offerings. Dismorr grew up in Hampstead and North West London (c.1897-1910) where the journey on the No.43 bus begins and the city she is mapping here is inevitably tied to personal memory and experience. An ulterior narrative of progression also lies beneath the surface of ‘June Night’; an aesthetic walk which is mimetic of Dismorr’s own development as an artist within the creative space of the city and its new avant-garde movements.

Rodengo has a multiplication of aesthetic identities as a Romantic, the ‘old poetry’ of Germany and a Latin Futurist. The narrator begins by expressing an ‘ardent admiration’ for all that Rodengo represents, suggesting that he is an ‘indispensable adjunct of the scenery.’ Yet as the narrator’s sense of independence grows throughout the vignette, Dismorr challenges the clichés of romanticism and our aesthetic expectations; the narrative voice steadily becomes more and more disillusioned by her chaperone’s Romantic affectations and his ‘infuriating lovesongs.’ By the end of ‘June Night’ she reflects that she has ‘lost’ her ‘taste’ for Rodengo’s ‘period,’ she breaks free from him to make her dérive into new aesthetic territories:

Surely I have had enough of romantics! their temperature is always above 98 ½ , and the accelerated pulse throbs in their touch. Cool normality and classicalism tempt me, and spacious streets of pale houses. At the next arret I leave you my friends, I leave you Rodengo with the rose in your ear. I escape from the unmannerly throbbing vehicle.

The passion of the romantics is hyperbolised as she moves from personal passion and emotion to aesthetic rationality. Out in the open streets the narrator is finally able to think for herself and to explore the aesthetic and artistic terrains which appeal to her personal desires.

The turn of the century witnessed what Lynne Walker has described as an ‘intense interest in town-planning’.[8] The advent of the Machine Age caused an increase in traffic and populace which had overwhelmed cities: new civic plans recognised that they needed to be restructured to reflect the adaptations taking place in modern life. Vorticism, which had ‘sprung up in the centre of this town’ of London, proclaimed in the first pages of its ‘Manifesto’ an interest in the development of modern cities.[9] Blast claims that the literature and art which it presents are part of the creation of a London Vortex; the re-conceptualisation and modernisation of the city from which it was born. However women were excluded from the developments being made to cities. While female architects were involved with domestic and small scale projects, they were not involved in the design of large scale public buildings or the redesign of cities. Dismorr’s participation in the movement of Vorticism gives her a feminist access to city spaces; while female architects cannot redesign London, Dismorr is able to re-write it.

The ‘squalor and glitter’ of romanticism transforms in the process of the dérive into a new architectural vision of the city:

I wander in the precincts of stately urban houses. Moonlight carves them in purity. The presence of these great and rectangular personalities is a medicine. They are the children of colossal restraint, they are the last word of prose. (Poetics, your day is over!) In admiring them I have put myself on the side of all severities. I seek the profoundest teachings of the inanimate. I feel the emotion of related shapes. Oh, discipline of ordered pilasters and porticoes! My volatility rests upon you as a swimmer hangs upon a rock.

Dismorr’s solid sentences without internal punctuation ‘carve’ her writing into ‘related shapes’ as though the sentences themselves are an architectural re-construction of the city she looks upon. The narrator proclaims ‘Poetics, your day is over!’ In Dismorr’s only conventionally prosaic piece, poetry is replaced by ‘the last word of prose;’ the narrator’s rebellion against the poetics of Romanticism is mimetic of Dismorr’s own literary choices as she ‘carves’ her sentences in ‘purity’ and explores a new prosaic and architectural form. As Dismorr’s narrator is taught the lessons of the ‘inanimate’ she develops as an artist. Instead of relating herself to abstract feelings and emotions, the narrator relates herself to the architecture of the space which she inhabits, projecting herself as a part of the very fabric of the city. Her ‘volatility’ is intimately entwined with the ‘emotion’ and ‘discipline’ of the world she finds before her. At this moment the city is completely open to Dismorr’s rewriting: it is a city which belongs to her narrator and which reflects, not a vision of patriarchal power structures as it did in ‘London Notes’, but a mirror image of our female narrator and the world as she perceives it. Dismorr has succeeded in making her chorographical map of ‘London Notes’ in to a personal and physical space where a woman’s presence can no longer be ignored or dismissed as merely transgressive.

[1] Janet Wolff, ‘The Invisible Flâneuse: Women and the Literature of Modernity’, in Feminine Sentences (Oxford, 1990), pp.34-47, Rachel Bowlby, ‘Women, Walking, Writing’ in Feminist Destinations (Edinburgh, 1997), p.191-219, Elizabeth Wilson, ‘The Invisible Flâneur’ in Postmodern cities and spaces (Oxford, 1996 (1995)), p.59-79

[2] Wolff, ‘The Invisible Flâneuse’ (1990) p.47

[3] Debord, in Situationist International Anthology , ed., Ken Knabb (California: Bureau of Public Secrets, 1981) p.50

[4] Debord, Situationist International (1981) p.51

[5] Debord, Situationist International (1981) p.51

[6] Heathcock, (1999) p.107

[7] See Rachel Bowlby, ‘Walking, Women, Writing’ (1997)

[8] Lynne Walker, ‘Architecture and Design: Heart of Empire/ Glorious Garden: Design, Class and Gender in Edwardian Britain’, in The Edwardian Era, ed. Jane Beckett and Deborah Cherry (London: Phaidon Press and Barbican Art Gallery, 1987) pp.117-137, p.127

[9] Wyndham Lewis’ final Vorticist publication The Caliph’s Design (1919) is confirmation of Vorticism’s conception of itself as an architectural movement calling, as it did, for the Vorticist aesthetic to be practically applied to the city.

Conclusion

Lewis wrote that man is ‘in a sense […] the houses, the railings, the bunting or absence of bunting. His beauty and justification is in a superficial exterior life’.[1] Dismorr’s contributions to Blast, a magazine distinctly of its cultural moment, show that women are also a part of the city, having an impact on its atmosphere and culture. While London offers predominantly patriarchal trajectories, as women walk or travel along prescribed and symbolic routes they make progressive movements forward, opening out new spaces of access. In Dismorr’s ‘June Night’ walking becomes an exploration and a renegotiation of the access available to women in the male city mapped in ‘London Notes’. The dérive of ‘June Night’ attempts to break through fields of exclusion for greater access: Dismorr’s written walk becomes a protest which exposes the oppressive bias of the patriarchal city. Her abstraction of monumental civic culture reduces its symbolism to basic gender polarities. Once we have only line and form it is possible to reconstruct the city and its male foundations in a written re-conceptualisation of London’s spaces.

Dismorr would continue to experiment with abstraction in landscapes and portraiture, exhibiting with the London Group and the 7 + 5 Society throughout the twenties and thirties. She also contributed other poems and critical pieces to other modernist magazines. Her work appears to become less radical and Dismorr did not publish any more fictional prose pieces but this only strengthens our sense of the importance of ‘June Night’ as a protest within its historical moment. Dismorr’s contributions to Blast present us with a city that belongs to her experiences and developments as a woman at a time when the Suffragettes were staging radical protests, and as an artist struggling to find an individual voice within a masculine movement. As war began to eclipse the importance of metropolitan art movements, The Blast War Number made a statement about its commitment to culture and experimentation: ‘This puce-coloured cockleshell will, however, try and brave the waves of blood, for the serious mission it has on the other side of World-war’ (p.5). Dismorr’s reconceptualization of London denies the war its silencing of female protest; Dismorr fights alongside Blast’s defence of art, but goes further, by defending the creative freedom of the female artist. Her radical architectural prose gives her a bold voice within her contemporary context and above all within studies of modernism.

[1] Wyndham Lewis, The Caliph’s Design, (Santa Barbara, 1986 (1919)) p.30

Bibliography

Edwards, Paul, ed., Blast 1 (UK: Thames and Hudson, 2009 (1914))

Lewis, Wyndham, ed, Blast No. 1: Review of the Great English Vortex (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, June 20th 1914)

Lewis, Wyndham,ed, Blast No. 2: The War Number (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, July 1915)

Lewis, Wyndham, The Caliph’s Design: Architects Where is your Vortex!, ed., Paul Edwards, (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1986 (1919))

Woolf, Virginia, ‘Street Haunting: A London Adventure’, in Street Haunting (London: Penguin Books, 2005 (1930)), pp.1-15

Woolf, Virginia, Mrs Dalloway, ed., Stella McNichol, introduction and notes by Elaine Showalter (London: Penguin Classics, 2000 (1925))

Woolf, Virginia, A Room of One’s Own (London: Penguin Books, 2004 (1928))

Woolf, Virginia, The London Scene: Six Essays on London Life (New York: Ecco, 2006 (1932))

Beckett, Jane and, Cherry, Deborah, ‘London’, in The Edwardian Era, ed. Jane Beckett and Deborah Cherry (London: Phaidon Press and Barbican Art Gallery, 1987), pp.36-41

Bowlby, Rachel, Feminist Destinations and Further Essays on Virginia Woolf (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997 (Virginia Woolf: Feminist Destinations published 1988))

Brewster, Dorothy, Virginia Woolf’s London (London: Geoge Allen and Unwin ltd, 1959)

Cork, Richard, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age: Volume 1, Origins and Development , and Volume 2, Synthesis and Decline (London: Gordon Fraser, 1976)

Edwards, Paul, ed., Blast: Vorticism 1914-1919 (Burlington, USA: Ashgate, 2000)

Grosz, Elizabeth, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994)

Grosz, Elizabeth, ‘Women, Chora, Dwelling’, in Postmodern Cities and Spaces, ed. Sophie Watson and Katherine Gibson Blackwell (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996 (1995)), pp.47-58

Grosz, Elizabeth, Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space (Cambridge, Mass: MIT, 2001)

Heathcock, Catherine, ‘Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939): Artist, Writer, Vorticist’ (unpublished thesis, Birmingham University, 1999)

Knabb, Ken, ed., Situationist International Anthology (California: Bureau of Public Secrets, 1981)

Le Corbusier, City of Tomorrow, translated from the 8th French Edition of Urbanisme with an introduction by Frederick Etchells (London: The Architectural press, 1971 (1924))

Lipke, William, ‘Jessica Dismorr’, in The Arts Review, Vol XVII No.8 (London: May 1-15 1965) p.10

Parsons, Deborah.L, Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City, and Modernity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000)

Roberts, William, The Vortex Pamphlets 1956-1958 (London: A Canale Publication, 1958)

Squier, Susan, ‘“The London Scene”: Gender and Class in Virginia Woolf’s London’, Twentieth Century Literature, Vol.29, No.4 (USA: Hofstra University, 1983), pp.488-500

Squier, Susan, Virginia Woolf and London: The Sexual Politics of the City (USA: The University of North Carolina Press, 1985)

Walker, Lynne, ‘Architecture and Design: Heart of Empire/ Glorious Garden: Design, Class and Gender in Edwardian Britain’, in The Edwardian Era, ed. Jane Beckett and Deborah Cherry (London: Phaidon Press and Barbican Art Gallery, 1987), pp.117-137

Weinreb, Ben, and, Hibbert, Christopher, ed., The London Encyclopaedia (London: Book Club Associates, 1985 (1983))

Wilson, Elizabeth, The Invisible Flaneur, in Postmodern Cities and Spaces, ed. Sophie Watson and Katherine Gibson Blackwell, (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996 (1995)), pp.59-79

Wolff, Janet, Feminine Sentences: Essays on Women and Culture (Oxford : Polity, 1990)