Earlier this year I was in a unfamiliar city for an interview for a job I was sure I wasn’t going to get. In the way I often do, I wandered into a bookshop in search of something like comfort – a new world into which I might retreat as I tried to forget the interview and let go of my anxiety about the wait for a decision. The book I chose was Marina Warner’s Forms of Enchantment, a collected volume of Warner’s sublime and fanciful writings on art and artists.

Back when I was in my early twenties Warner was a hero of mine. I loved fairy stories, folk tales, and their re-imaginings, I was obsessed with the art of Paula Rego, with exploring ideas of mythmaking and feminism. And, as I was testing out ideas about who I might become and what I might do with my life, I spent a lot of evenings and weekends writing art reviews in the lonely city I had recently moved to.

In the preface to her book Warner writes that she wishes to ‘argue for writerly ways of exploring art, as developed in literary tradition’. She goes on to argue that:

‘When I write about artworks and the artists who made them, I try to unite my imagination with theirs in an act of absorption that corresponds to the intrinsic pleasure of looking at art. Since the Greeks, ekphrasis has offered a way of capturing visual experience in words – but while I believe in close looking, description is not enough. I like to explore above all the range of allusions to stories and symbols; not to pin down the artwork as if it were a thesis or a piece of code, but to touch the springs of the work’s power. Art writing at its most useful should share in the dynamism, fluidity and passions of the objects of its inquiry.’ (pp. 8-9)

I love that phrase – ‘to touch the spring’s of the work’s power’ – because it suggests the liveliness of the work of art, its dynamic status as something still in process, as a thing with a resonance and agency all its own, waiting to meet the mind that extends towards it. Reading Warner’s collected art writings felt comforting and nostalgic: these words were familiar treasure ranging across subjects as diverse as Hieronymus Bosch, Tacita Dean, Helen Chadwick and Sigmar Polke. But in reading Warner’s work I also felt something like regret, or perhaps it was even jealousy: a slightly existential feeling of paths taken and those diverted from. Although I recognised the pleasure conveyed in Warner’s words, they seemed to more readily apply to my relationship with literary texts in my recent critical and academic writings: close reading rather than close looking. I remembered the pleasure of writing about art as an ‘act of absorption’, as Warner describes it, but it was a distant memory. I had a vision of myself in my early twenties on assignment for The Hackney Citizen, wandering the streets and galleries of east London and filing copy from coffee shops. Once upon a time I’d interviewed Conrad Ventur for Garageland magazine, reviewed shows by Georgia Hayes and art festivals in Aldeburgh, and even written catalogue essays for galleries in Berlin. What had I lost or left behind when I stopped doing this kind of writing?

All of this is a circuitous, expanded way of saying that when Corridor8 asked me to review an exhibition for their brilliant online publication, I leapt at the chance. Back in October I caught the train to Preston as the damp, warm, grey air was burnt to a blaze of blue by the autumn sun, to review ‘The Pearls and the Oyster’ at the Birley Studios. You can read the review I wrote about the show here.

I bought a new notebook on the way in, chatted with the curator Jayne Simpson in the sun-filled gallery, and spent a very long time absorbed in the worlds of each of the thirteen paintings of this group show, making notes and wondering where this act of close looking might take me.

I’m just getting warmed up and hope I might have the chance to do something similar again:

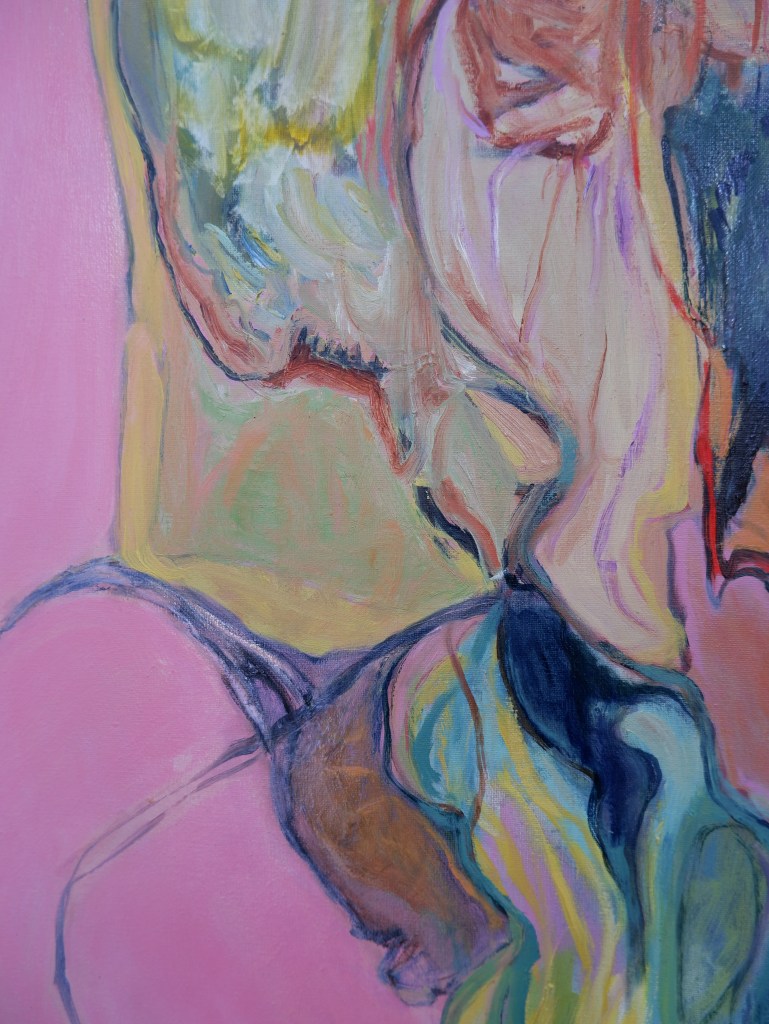

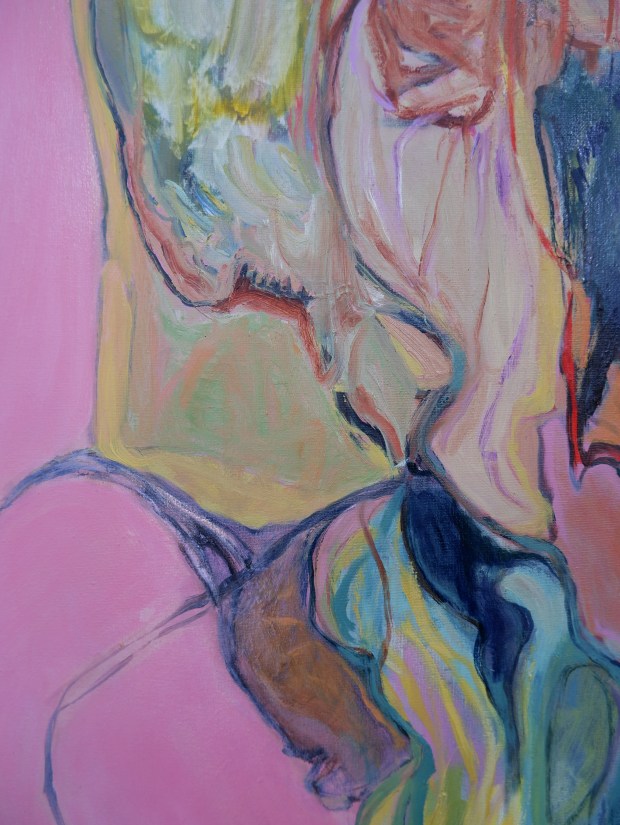

What I enjoyed most about this exhibition was the opportunity to look closely and to see where that looking might take me. The ventilation shafts of the tunnels under the Mersey in Liverpool can have a surreal, space-age quality to them, but Payne’s ‘Shaft 1’ (2019), spray-painted with oil on concrete, brilliantly emphasises their dilapidated mundanity. The photo-realist quality of Payne’s work is challenged by an interest in the texture and characteristics of both medium and subject. Paint chipped or scraped from the surface of her concrete canvas replicates (or replaces) the peeling paintwork of the building depicted; the bubbling of paint in the muted sky might give us the sense that we are really looking at the concrete surface of Shaft 1 and not a depiction of it. Where does the painting end and the world begin? At the other end of the spectrum is Nancy Collantine’s ‘Para-Fantasia’ (2024), a painting whose abstract voluptuousness resists any attempt to find definitive signs in the cascade of colour, line and pattern that tumbles down the canvas over a tectonic plane of pink. Sometimes I think I catch a figure, a face, a landscape, and then the painting seems to rearrange itself again before my eyes.