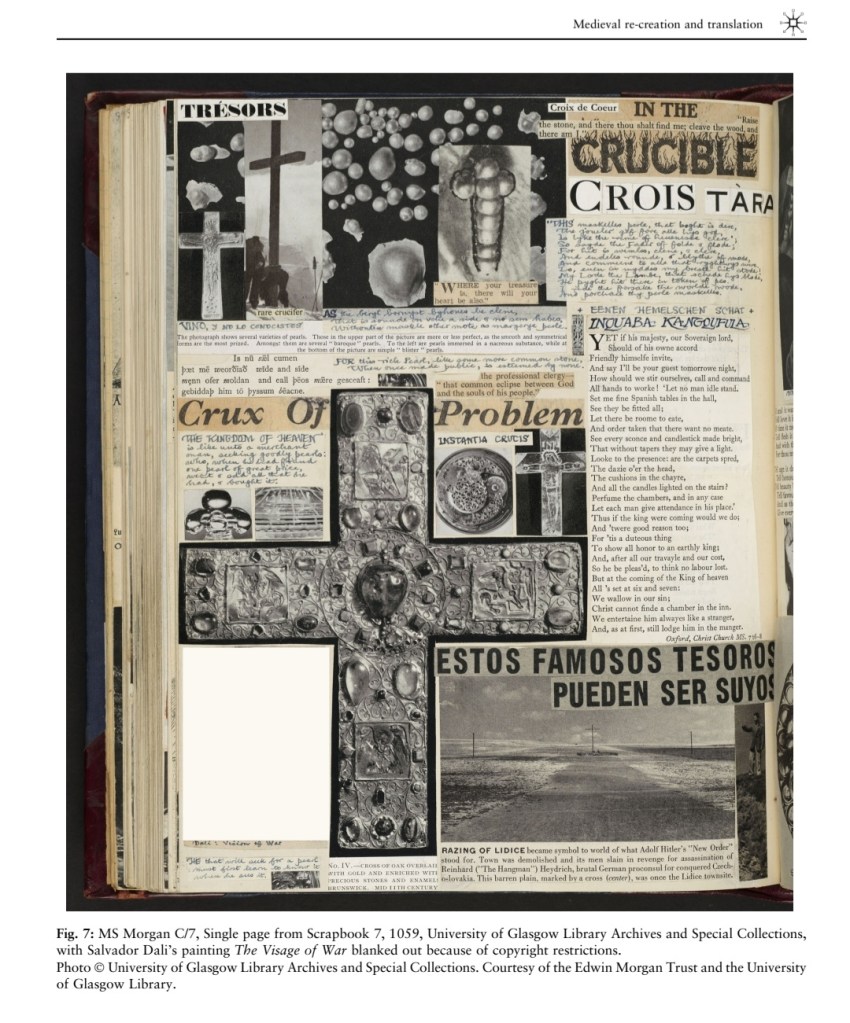

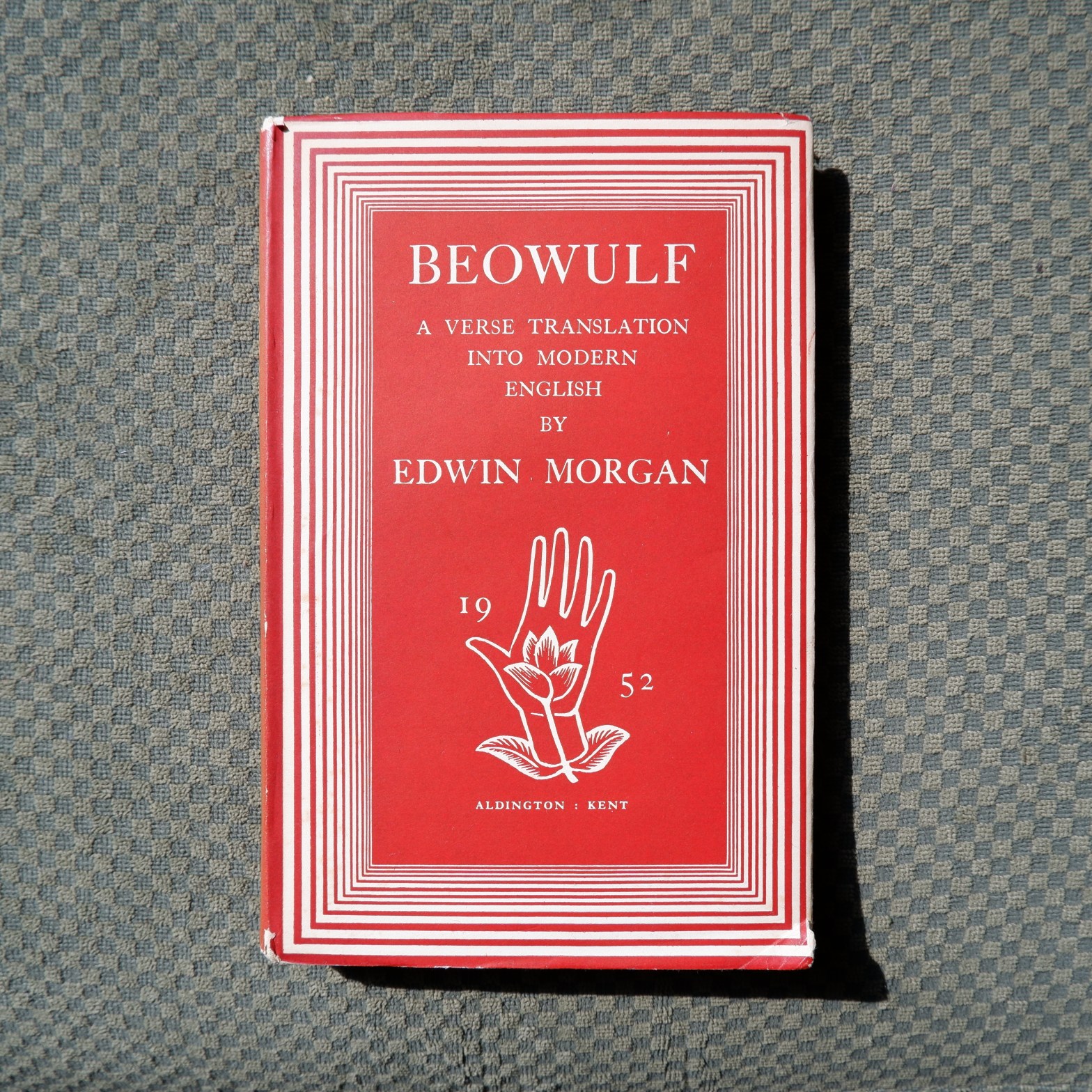

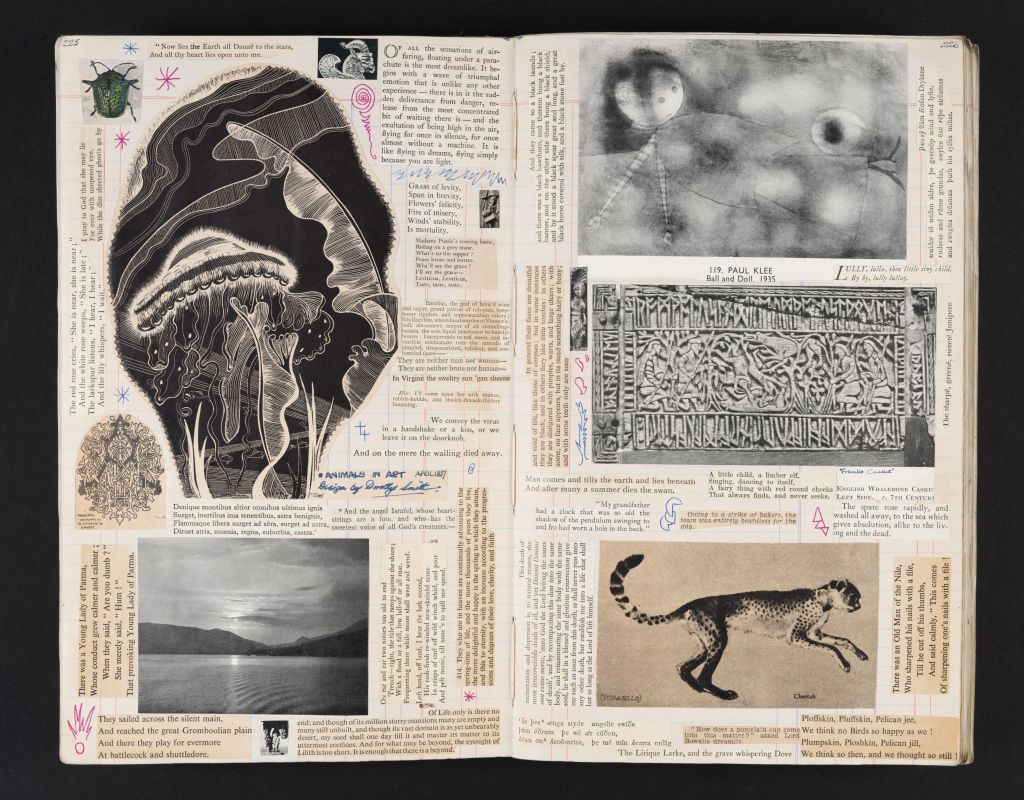

I have a longish essay in the current issue of PN Review (295), ‘A Quest for the Camaldolese Grail in the Footsteps of Lynette Roberts’. It’s the first thing I’ve had published about the Argentine-born, Welsh writer Lynette Roberts (1909-95), who is one of the subjects of my current research project on ‘Haunted Archives’ and women rewriting the medieval past. The essay is about access to cultural heritage, impostor syndrome, material and sensorial encounters with medieval manuscripts, and the fascinating writing life of Roberts herself.

I thought I would share a brief post here with some images of the Camaldolese Grail (the subject of my quest and of Roberts’ parallel quest in the 1940s), as the piece is unillustrated in PN Review. The Camaldolese Grail (or Gradual) is a stunning illuminated fourteenth-century manuscript from Italy, now held by the Victoria And Albert Museum Art Library. I went to see it after reading Roberts’ essay on the manuscript (published in the 1940s in a journal known as Life & Letters) and took great pleasure in spending time with this gorgeous, gilded object.

Here’s a little snippet from the essay, demonstrating why Roberts’ essay had filled me with such curiosity:

‘Roberts writes about mushroom shades and mole tones and pink blancmange rocks. She draws our attention to the lines on a lake which do not depict ice, although she might forgive us for thinking so, but as she describes them appear to curve ‘like bleached seaweed, oriental eyelashes, or flayed wheat’. Arguing for why she thinks we see Lorenzo Monaco’s hand in this ostentatious, gilded manuscript, she writes that ‘[t]he miniatures which I have studied have the same pink blanc-mange rocks, the dark polished trees, lined haloes, heavy eye-shadow, and drooping mouths terminating in small dots’ of the paintings she has observed in the National Gallery. Roberts doesn’t simply describe the manuscript. She uses her poet’s eye to vividly evoke her aesthetic and material encounter with this sacred object, producing a surreal portrait of a book that seems to distort time under her gaze.’

My visit to the Art Library didn’t go perfectly smoothly, however, and it was this experience of fear, trepidation, and even shame, as well as what this revealed about the significance of Roberts’s own encounter with the manuscript, that became the focus of the essay. I don’t want to repeat the story here (you’ll have to buy a copy of the journal), but what I initially ordered in the library wasn’t the manuscript at all – it was an itemised collection of waste materials from the manuscript’s restoration in 2009!

If you’ve never heard of Lynette Roberts before, and haven’t read any of her poetry, then you’re in for a treat, as Carcanet are publishing a new and expanded edition of her poems next month.